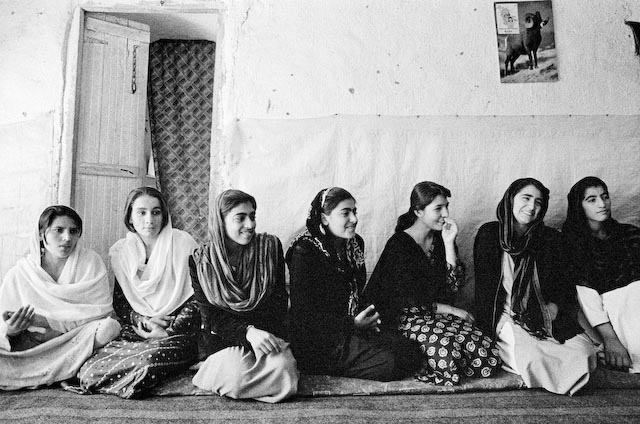

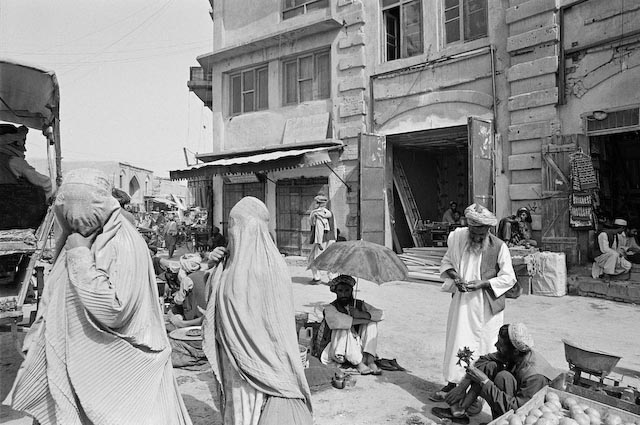

Remembering the People of Afghanistan

photograpy by Babrak salary

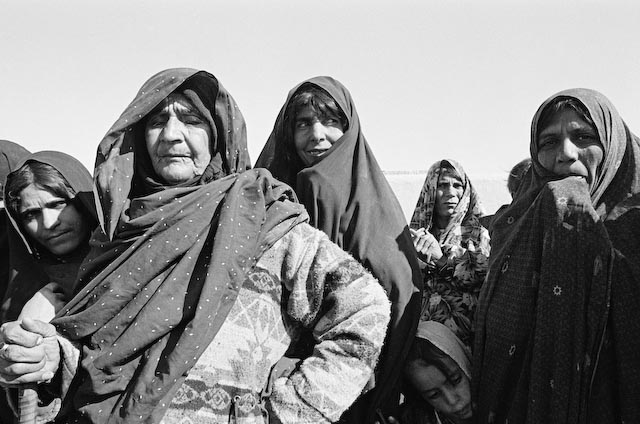

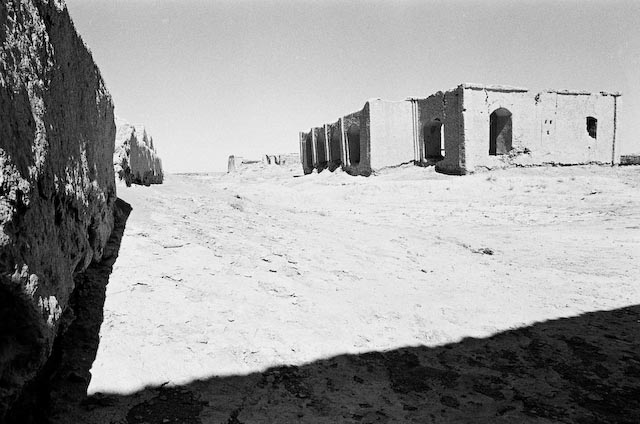

I went to Afghanistan seven years ago, in 2002, as a photographer to document the medical aid of Médecins du Monde Canada, only a few months after the military invasion of the US-led coalition forces. My reaction was one of shock and disbelief at the extent of the misery, poverty and dislocation of the Afghan people. The level of anguish and destruction is burned into my memory.

The stated objectives of the invading Western powers, operating under the umbrella of NATO, were to fight terrorism and “eradicate” Al-Qaeda and their allies, the Taliban; to establish democracy in Afghanistan; and most importantly, to reconstruct this country that has been ruined by more than two decades of continual war.

After more than seven years of military action

After more than seven years of military action which has ravaged the country and taken thousands of lives, the NATO forces have had few positive results. Still more tragically, the heavy price paid by the Afghan people has been virtually forgotten by the media. Instead, coverage has focused mainly on the casualties of the invading Western forces, the caskets coming home. The silence on the human cost of this futile war, and the contradiction between its objectives and its outcome have spurred me to return to my photos of seven years ago. Looking at them again after so many years, they arouse my deepest sorrow for this people tormented and stifled by occupation and war.

In examining the record of this war over the past seven years, one can say that none of the stated promises and objectives of the invading powers have been fulfilled. Today, we are witnessing a resurgence of the Taliban, who operate in 72% of Afghanistan and control the main arteries that lead to the capital, Kabuli.

Instead of establishing democracy

Instead of establishing democracy, the invading powers have made a pact with some of the Taliban, warlords and drug dealers, restoring the Taliban to power in most provinces which has resulted in the blatant violation of the civil rights of Afghans and particularly those of women. Except the slight reprieve found in Kabul, in almost all other parts of Afghanistan women still live under the repressive and dehumanizing laws and regulations of the Taliban era. For them and many others there has been no significant progress towards peace, democracy and prosperity.

The invading countries also present a dismal record regarding the reconstruction of this country. The majority of Afghans still live a daily life of destitution, hunger, disease and dislocation. By 2011, the year Canadian troops should withdraw, the Canadian government will have spent between $14 and $18 billionii, the bulk of which, so far, has gone to maintain military operations and enrich the corrupt government installed in Kabul. While the general population suffers the consequences of the war, the newly rich live a life of luxury courtesy of the Western powers.

I came into contact with refugees from Afghanistan in 1982 in Quetta, Pakistan. Though a huge number of Afghan refugees had been living in Iran for several years, this was my first intimate experience with the nation with whom Iranians share the same language, religion and cultural background. I had escaped the political repression and massacre of the Revolution in Iran and Quetta was the first stop in my long journey of political exile. For forty-five days two Afghan brothers, refugees of the Soviet invasion, hosted me and another Iranian political activist. I was deeply moved by their resilience and generosity, as well as their suffering. Twenty years later, my return to the same city in Pakistan, en route to Afghanistan, revived many memories of the two brothers and the plight of Afghan refugees. However, during my two months in Afghanistan and the refugee camps in Pakistan, my most disturbing memories of Iran were surpassed by the bitter realities I witnessed.

There are four people, all of whom I met the week I left Afghanistan, whose stories I want to pass on. They are a small sample of life in this country. On March 18, 2002, I went to visit the cemetery in the city of Zaranj as part of my project. While I was taking photos in the silence of the graveyard, an adolescent boy around seventeen years old approached me asking for money. Where his hand had been was a bloodied bandage. I asked him what had happened. “The Taliban cut off my hand a few months ago, as punishment for stealing.”

His mother had killed his father, and according to a strict interpretation of Islamic law, was condemned to death. The loss of both parents left him destitute, stealing food to survive.

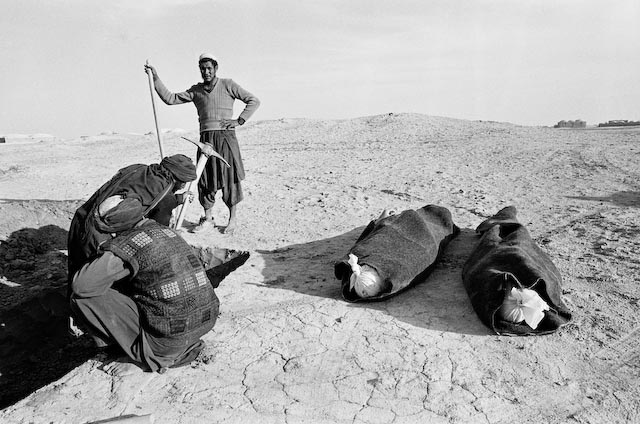

“One day I was caught, arrested and sentenced.” While I was listening, a truck honked from across the enormous cemetery. In the back of the pickup there were bodies, fourteen in total. The young man next to the truck said that eleven of them were his friends and relatives from his village in north-western Afghanistan. The remaining three he didn’t know; they were from another province. Like many Afghans over the past thirty years, the young man, twenty-five years old, had gone to Iran because there was no work in his village. From abroad he could support his wife, parents, his sister and two brothers.

He had been working in Iran as a day-labourer for over a year when he heard that his family was starving: the drought had left them with no food. He went home with his savings, the equivalent of $500 US. After three months, he found no work beyond that of subsistence level, so he decided to return to Iran with his family where they could work and have enough food. In the end, twenty-five friends and relatives decided to come with him. On their journey south, eight days in a truck, they stopped at a samovar (a café). Two men approached them and offered to take the group across the border for $25 US each, to be paid after their arrival. They were joined by another twenty-seven people and, in the middle of the night, the smugglers took the fifty-two Afghans to the border near Zaranj.

The Helmand river, now almost dry, runs along the border. In 2002, at only one point was the river deep enough that one needed to swim or have a boat to cross it. Because of the drought, the rest of the river was shallow enough to cross without getting wet.

The smugglers led the group to the river and began to walk across, but the river quickly became deep. Many people couldn’t swim; the young man clung to a branch to keep him afloat. Afghan border guards arrived, but by then the screams had stopped. Four of the fifty-two made it across and entered Iran. Eleven survived, including the young man. The rest fled in search of other border crossings. In the morning, fourteen bodies were found in the river.

Local doctors said the cause of death was drowning, but a joint mission of the United Nations and Médecins Sans Frontières asked to see the bodies. The case was closed because the doctor did not have the proper facilities to conduct a full autopsy. However, it was concluded that the cause of death was not drowning: several of the deceased had pupils of different sizes which indicated possible violence to the head; some had white froth in their mouths, a sign of possible poisoning; and none of the bodies showed evidence of having been in the water for several hours. Their outstretched arms could not be explained. Some locals claimed that Iranian agents had electrocuted or suffocated them and later thrown them in the river.

The young man vowed he would never try to illegally cross the border to Iran again. He buried his friends and family. The border between Afghanistan and Iran is rife with similar stories that have been happening, repeatedly, for many years.

Later that week, in Zaranj, I went to a house shared by six families: widowed mothers, fatherless children, and orphans. I approached one mother who was sitting quietly in a corner and asked her about her children. She said she had four children, but the fourth one was missing. We had been talking for a while when she looked down abruptly and said,“I sold my daughter.”

“What do you mean you sold her?”

“For $282 US. To a man from Pakistan.”

“How old was she?”

“Fourteen.”

“Why?”

She turned her head and looked at her three hungry children. She went silent and started to cry.

“Have you heard from her since then?”

“No.”

Because of the lack of economic means, even subsistence-level means, many Afghans have resorted to the sex trade as a source of income; it is common knowledge in Afghanistan that young girls are a valuable commodity.

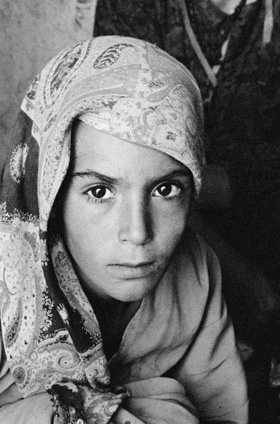

The following day I visited another similar house where I came across another story: that of a seven-year-old girl who had lost her father after the fall of the Taliban. As I was talking to her mother, she was sitting on the ground, curled up, looking away from us. Her mother said she had been silent since the death of her father. The girl turned and looked at me. I was struck by her intensity and her serious eyes that scrutinized me. She seemed to be asking why I was there, even physically. This marked a unique moment, unparalleled in those two months. It affected me so much that I questioned my ability to capture the essence of that moment and transform it into an image. I realized then the limitations of photography in capturing and reflecting the depth of human suffering.

Where are the people of Afghanistan?

After more than seven years, many questions regarding Afghanistan are still with us: Where are the people of Afghanistan? What has happened to them? are two important ones. The life of the Afghans has deteriorated, not improved, and their plight, for the most part, has been left by the way side by the media. Of the five thousand images I took of the people of Afghanistan, this book is but a glimpse of their reality which will, I hope, bring the issues surrounding this war to the fore of the public arena.

Babak Salari

Montreal, January 2009